Transit of Venus 2012

May 2012

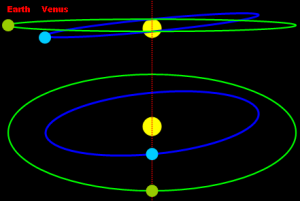

On the 6th of June 2012, Venus was seen from Earth to transit across the face of the Sun. While Venus is larger than Earth's Moon, it is much further away from us and much closer to the Sun. During a transit, Venus only eclipses a small part of the Sun's face. Nonetheless, its silhouette is large enough to be easily seen from the Earth. This event happens twice in roughly every century when Venus happens to cross the line between the Earth and the Sun. The orbital paths of Venus and Earth are slightly at an angle to each other, which is why this occurs so rarely. (See the figures below and the Wikipedia page on the Transit of Venus for more detail.)

The silhouette of Venus' disk on the Sun in 2004. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Illustration of the differing angles of the orbits of Earth and Venus. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The 2012 transit was not best placed for observers in the UK, with only the last 50 minutes of the event being visible from sunrise at 4:30 am on June 6th. HCO Project Engineer Andrew Baxter was brave enough to get up at that time, and managed to get this excellent photo:

The 2012 Venus transit observed by HCO Project Engineer, Andrew Baxter

The last time this phenomenon was seen this century was 2004, when HCO and the Oxford Museum of the History of Science held a public transit-watching event in University Parks (see below for more on this). Before that, the last two transits were in 1874 and 1882. The phenomenon will not occur again until 2117. The ground- and space-based solar observatories of the present century have allowed the 2004 and 2012 transits to be observed in unprecedented detail. As explained later, precise observations of the transit of Venus can be useful in studies of extrasolar planets.

HCO Transit of Venus event, University Parks, Oxford, 2004

Quite unexpectedly, this turned out to be one of the largest public transit-watching events in the U.K. - indeed, quite possibly the largest such formally organised public viewing of the transit, other than that at Greenwich. The transit-watch was run in Oxford by the Hanwell Community Observatory in partnership with the Museum of the History of Science, the event itself taking place in the University Parks, 10a.m. - 12.30, on the 8th June. HCO provided 50 pairs of BAA 'eclipse spectacles', one portable refractor set up for projection and three portable 4" refractors for direct observation through full-aperture solar filters. The Museum promoted the event in association with their exhibition on the 18th century transits and provided some large display boards in the Parks on the day; a large proportion of the personnel of both institutions turned out to run the event itself. Conditions were near perfect (and scorching, at over 30° C!) and the transit was followed continuously throughout the period of the watch. Even so, the public turnout was staggering: having expected maybe up to a few hundred if the day was fine, we were all amazed at a final count of approaching 2000. Virtually everyone saw the projected image of the Sun and Venus and had a turn at the eyepiece, despite queues approaching 150 yards long at times. This was all on an unenclosed site, and admission was free.

Andrew shows a visitor the transit through a portable refractor with a solar filter

The whole of this wonderful gathering seems to have passed off with great good humour and patience on the part of our visitors and a real sense of occasion, truly a triumph of public astronomy! This was certainly the largest such event that Oxford has seen for any astronomical phenomenon for very many years, an outcome that none of our team had expected for a moment. This and the other large turnouts around the country on 8th June are surely object-lessons in the potential for public outreach in astronomy.

Inspired by his experience at the event, Nicolas Jacobs, a former Fellow and Tutor of English at Jesus College, wrote this wonderful poem:

Transit of Venus

for A.M.

An annual event, were orbits only

locked in a single plan. As it is,

a lifetime could go by, without

your ever seeing it. Come to that,

you dare never even try. Forget

the eclipses you can at least glimpse

for a moment: the bitten sun, the blank

presence of the unseen moon

as the air cools, grown suddenly

still, the birds silenced. Less plain

or simple this conjunction. Nature

takes no notice. Too small to see

without staring, the last thing ever

seen, if stared at: only projected

on paper can you watch this dusky

star, obscurely and from behind,

move imperceptibly over the bright

disc. All round, crowds, summery.

The voices. And the silent motion -

now, again in eight years, and that,

for us, will be all. In some parallel

universe, where ecliptics align,

are they smiling, to see us make

such fuss over such a little thing?

Transits of Mercury and more!

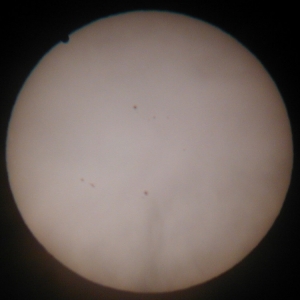

Venus isn't the only planet which is seen (from Earth) to transit the Sun. Mercury, being the only other planet inside the Earth's orbit, transits 13-14 times a century, the last time being 2006. HCO Director Christopher Taylor observed Mercury's transit in 2003 and took a sequence of photos:

Click here for a larger version

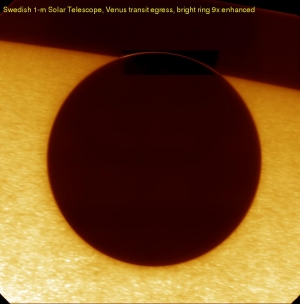

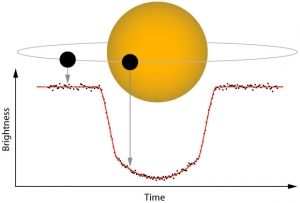

Transits are one of the ways astronomers find exoplanets around other stars. When a planet passes in front of its host star in our line-of-sight, as Venus does the Sun, some of that stars light is blocked, causing a dip in its light over time (see diagram below). The shape and depth of the dip in the observed "lightcurve" can reveal properties about the planet, such as its size and orbital period. By observing an exoplanet transit with a spectrograph, it is also possible to tell what gasses are in its atmosphere through the colours of the starlight that are absorbed. You should be able to see in the image of the 2004 transit of Venus below, from the Swedish 1 metre solar telescope, the way that the Sun's light is refracted through the atmosphere of the planet. The transit of Venus is an important event to astronomers on Earth, as it can help us calibrate our methods for making such measurements of exoplanets.

Credit: Institute of Astronomy, University of Hawaii

Venus leaving the disk of the Sun, observed by the Swedish 1 metre Solar Telescope, 8th June 2004.

Credit: Institute for Solar Physics, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.